【综述】| 肿瘤相关中性粒细胞在乳腺癌发生、发展中的作用研究进展

时间:2024-11-08 20:00:38 热度:37.1℃ 作者:网络

[摘要] 中性粒细胞起源于骨髓,由骨髓干细胞增殖分化形成,是血液循环中最常见的多形核白细胞,约占成人外周血白细胞总数的70%。中性粒细胞也是人体内寿命较短的细胞之一,正常成人外周血中性粒细胞半衰期仅数小时,依赖骨髓的不断补充维持中性粒细胞的数量稳定。作为固有免疫系统的短效效应细胞,中性粒细胞参与多种炎症和免疫过程,并构建抵抗感染的第一道防线,在激活和调节先天性及适应性免疫反应中发挥着至关重要的作用。虽然过去人们普遍认为中性粒细胞主要与急、慢性炎症和抗感染过程相关,而由于其寿命较短和不可增殖的特性,一度忽视了其在癌症中的作用。如今越来越多的研究表明,中性粒细胞在癌症中的作用远超以往的认知。乳腺癌是女性常见的恶性肿瘤之一,其发病率和死亡率均位居女性恶性肿瘤的前列。全球范围内乳腺癌的发病率逐年升高,严重威胁全世界女性的身心健康。最近有研究证实,肿瘤相关中性粒细胞(tumor-associated neutrophils,TANs)已成为肿瘤微环境(tumor microenvironment,TME)的重要组成部分,在乳腺癌的发生、发展和转移过程中均发挥重要作用。TANs是由多种肿瘤源性细胞因子相互作用,刺激诱导中性粒细胞募集至TME中积累形成的。中性粒细胞的强可塑性和多样性赋予TANs促进和抑制肿瘤的双重潜能。TANs可通过促进肿瘤生长和转移、推动肿瘤新生血管生成、免疫抑制和生成中性粒细胞胞外诱捕网(neutrophil extracellular traps,NET)来促进乳腺癌进展。反之,TANs也可通过直接杀伤肿瘤细胞和参与形成抗肿瘤的免疫网络间接介导抗肿瘤反应。TANs相关的乳腺癌治疗已逐步成为研究热点,尤其是在三阴性乳腺癌(triple-negative breast cancer,TNBC)中。本综述回顾乳腺癌中TANs起源、形成、分型和功能机制方面的研究进展,并详细阐述TANs与乳腺癌的临床相关性,进一步结合近期乳腺癌中TANs的相关临床研究,系统总结针对乳腺癌患者靶向TANs的治疗策略,以期为乳腺癌中TANs作用机制研究和乳腺癌治疗提供新思路。

[关键词] 肿瘤相关中性粒细胞;乳腺癌;免疫治疗

[Abstract] Neutrophils originate from the bone marrow, differentiating from hematopoietic stem cells, and are the most prevalent polymorphonuclear leukocytes in the blood, accounting for approximately 70% of the total white blood cells in adult peripheral blood. Neutrophils are recognized as one of the relatively short-lived cells in the body, with a normal half-life of just a few hours in the peripheral blood, which rely on continuous replenishment from the bone marrow to maintain the number. As short-lived effectors of the innate immune system, neutrophils participate in various inflammatory and immune processes, and constitute the first line of defense against infection, playing a crucial role in the activation and regulation of both innate and adaptive immunity. Neutrophils were once considered as key effectors of inflammation and infection. Because of their short lifespan and non-proliferative nature, the role of neutrophils in cancer was overlooked. Their role in cancer has been increasingly recognized in recent years. However, more and more studies demonstrate that neutrophils play a much more significant role in cancer than previously thought. Breast cancer is one of the common malignant tumors in women, and its morbidity and mortality are in the forefront of female malignant tumors. The incidence of breast cancer is rising globally, posing a severe threat to the physical and mental health of women worldwide. Recent studies confirm that tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) have become a critical component of the tumor microenvironment (TME) and play a significant role in the development, progression and metastasis of breast cancer. TANs are formed via the interaction of various tumor-derived cytokines which stimulate and recruit neutrophils to accumulate in the TME. The strong plasticity and diversity of neutrophils endow TANs with dual potential to both promote and inhibit tumors. TANs advance breast cancer progression by promoting tumor growth and metastasis, supporting tumor angiogenesis, immune suppression, and generating neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs). Conversely, TANs mediate antitumor responses through direct tumor cell killing and contributing to the formation of antitumor immune network. Research on TANs-related breast cancer therapies, particularly in triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), has become a research hotspot. This review summarized recent advances in the origin, formation, classification and function of TANs in breast cancer, as well as a detailed discussion of their clinical relevance. We further combined recent clinical studies to systematically summarize the treatment strategies targeting TANs in breast cancer, with the aim of providing new insights into the functional mechanisms of TANs and the treatment of breast cancer.

[Key words] Tumor-associated neutrophils; Breast cancer; Immunotherapy

中性粒细胞是血液循环中最丰富的白细胞类型,也是主要的免疫细胞[1-2],在先天性和适应性免疫反应中均发挥着重要作用。但其寿命较短,半衰期仅为数小时[3]。中性粒细胞较短的寿命和不可增殖的特点导致既往人们低估了其在癌症中的重要性,而如今越来越多的研究证实中性粒细胞在癌症的发生、发展过程中扮演着复杂的角色。肿瘤微环境(tumor microenvironment,TME)中各种肿瘤源性趋化因子相互作用,诱导中性粒细胞募集形成肿瘤相关中性粒细胞(tumor-associated neutrophils,TANs)[4]。TME中恶劣的细胞生存环境(如低氧、低pH等)和免疫抑制环境赋予了TANs促肿瘤特性。然而TANs也具有抗肿瘤特性,可通过直接杀伤或间接激活适应性免疫反应抑制癌症进展[2]。

乳腺癌是由乳腺上皮细胞增殖失控形成的恶性肿瘤,其发病率位居全球女性恶性肿瘤的前列,也是女性肿瘤相关死亡的主要原因[5]。在过去10年中,TANs逐渐被认为是影响乳腺癌患者预后的关键因素之一,尤其是在三阴性乳腺癌(triple-negative breast cancer,TNBC)亚型中[6]。本综述总结近期TANs在乳腺癌发生、发展中的复杂机制和免疫治疗的研究进展,揭示针对TANs的乳腺癌治疗靶点,以期为乳腺癌的治疗提供新思路。

1 TANs的起源和募集

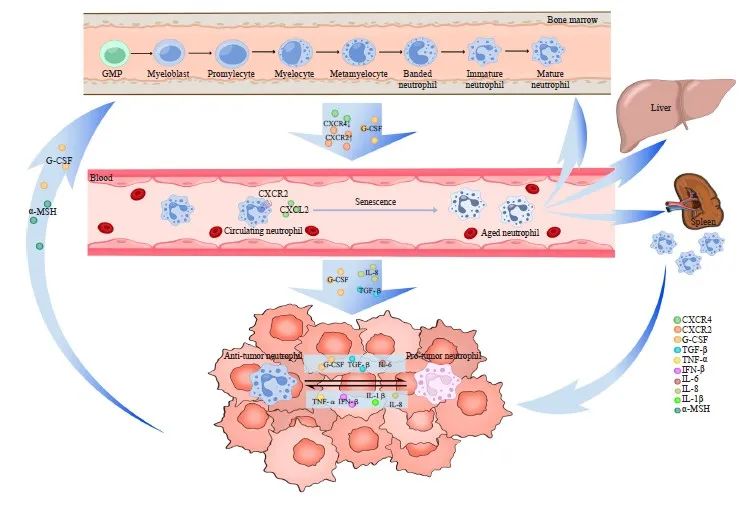

TANs的形成主要包括中性粒细胞在骨髓中增殖成熟,释放到外周血循环,以及趋化运动至肿瘤微部位3个阶段(图1)。所有的中性粒细胞均起源于骨髓中的多能粒细胞-单核细胞祖细胞(granulocyte-monocyte progenitor,GMP),随后经过原粒细胞、早幼粒细胞、带状核细胞和分叶核中性粒细胞等多个阶段,最终形成成熟中性粒细胞[7]。成熟中性粒细胞在粒细胞集落刺激因子(granulocyte colony-stimulating factor,G-CSF)的刺激下从骨髓释放进入外周血循环[8],CXC族趋化因子受体2(CXC chemokine receptor 2,CXCR2)和CXCR4也参与调节该过程。正常生理状态下只有成熟中性粒细胞会释放到外周血循环中,但在组织损伤或严重感染时人体对粒细胞需求增加,引起紧急粒细胞生成,未成熟和成熟中性粒细胞释放到外周血循环中的数量均会增加[9]。

进入外周血循环的中性粒细胞遵循昼夜节律,从新鲜中性粒细胞老化形成老年中性粒细胞。昼夜节律相关基因Bmal1调节该过程,通过诱导中性粒细胞表达CXC族趋化因子配体2(CXC chemokine ligande 2,CXCL2)并与CXCR2结合启动老化[10]。老年中性粒细胞返回骨髓、肝脏或脾脏,在其生命周期结束时被巨噬细胞清除。正常生理情况下,进入外周血循环的新鲜中性粒细胞与凋亡的老年中性粒细胞数保持平衡,保证循环内的中性粒细胞计数恒定[11]。

过去普遍认为炎症是组织招募中性粒细胞的关键因素,白细胞介素8(interleukin-8,IL-8)等炎症信号释放到循环中,诱导中性粒细胞趋化至目标组织[12]。近期研究[13]发现肿瘤与炎症在招募中性粒细胞的机制上有很多共通之处,这为我们从炎症角度挖掘乳腺癌中TANs的相关作用机制提供了可能。值得注意的是,肿瘤不仅诱导循环内的中性粒细胞,还可通过直接干预TANs的源头—骨髓中的髓系祖细胞来诱导TANs的招募。肿瘤源性G-CSF促进骨髓中造血干细胞的增殖和分化,使造血分化向髓系谱系倾斜[14]。Xu等[15]研究发现,肿瘤可通过下丘脑-垂体轴远距离调控垂体释放α-促黑素细胞激素(α-melanocyte-stimulating hormone,α-MSH),促进髓系祖细胞的扩增,进而促进TANs等免疫细胞的生成。

此外,中性粒细胞的迁移并不遵循严格的单向途径,迁移至炎症部位的中性粒细胞还可以反向迁入血液循环[16]。那么肿瘤招募的TANs是否会在TME中获得促肿瘤特性后再度迁入血液循环诱导肿瘤的远处器官转移?这需要研究者进一步探索原发肿瘤灶、肿瘤转移灶及循环中性粒细胞的表型和来源关系。除了骨髓来源的TAN外,作为单核细胞储库的脾脏也能够为TME提供TANs[17]。不过目前尚不确定骨髓和脾脏来源TANs的表型和招募过程是否存在差异,仍需进一步探索。

图1 TANs的形成及功能示意图

Fig. 1 The formation and function of TANs

Neutrophils are derived from multipotent GMP located in the bone marrow, where they proliferate and mature into mature neutrophils before entering peripheral blood circulation. Within this circulation, neutrophils undergo aging processes to become aged neutrophils, which subsequently migrate back to the bone marrow, liver, and spleen for phagocytosis by macrophages. Various tumor-derived cytokines facilitate the recruitment of neutrophils into the TME, resulting in the formation of TANs. Additionally, tumor cells directly influence bone marrow activity to modulate TANs recruitment. TANs exhibit a dual role both promotes and inhibits tumor growth and dynamically convert between these two functional phenotypes through polarization. Numerous tumor-derived cytokines are involved in mediating this polarization effect.

2 TANs的分型和极化

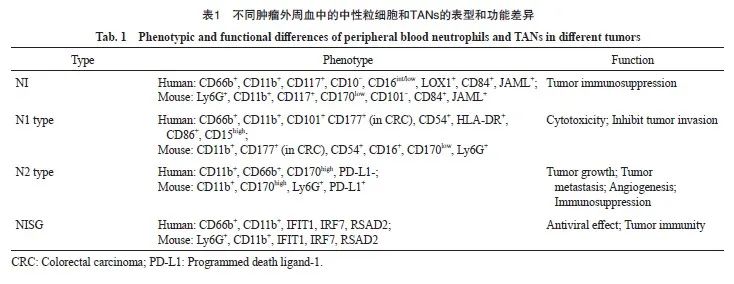

与肿瘤相关巨噬细胞(tumor-associated macrophage,TAM)类似,TANs在TME中也表现出促进和抑制肿瘤的双重潜能,并通过极化转变其功能。2009年Fridlender等[18]参考TAMs的分型方式,将TANs分成抗肿瘤型(N1型)和促肿瘤型(N2型)。尽管这种二分法过去对TANs的研究具有很大帮助,但随着多组学等新技术的面世,越来越多的证据表明二分法不足以涵盖TANs的众多表型和功能。Jaillon等[2]根据TANs表型的差异,将TANs分为未成熟中性粒细胞(immature neutrophil,NI)、抗肿瘤型(N1型)、促肿瘤型(N2型)和具有干扰素刺激基因特征的中性粒细胞(neutrophil with interferon-stimulated gene signature,NISG)4种类型(表1)。但随着TANs功能表型的不断发现,其分型标准也亟待进一步更新。

TANs在TME中的功能并非固定的,TANs通过极化过程在促肿瘤和抗肿瘤两种形态间互相转化[19],肿瘤源性的细胞因子在诱导该过程中发挥重要作用。肿瘤源性的转化生长因子-β(transforming growth factor-β,TGF-β)、IL-6和G-CSF等细胞因子诱导TANs向N2型极化,而干扰素β(interferon-β,IFN-β)、IL-1β、IL-8(CXCL8)和肿瘤坏死因子-α(tumor necrosis factor-α,TNF-α)等诱导TANs向N1型极化[20]。TANs的极化不只局限在TME内,Casbon等[23]在小鼠乳腺癌模型中发现肿瘤源性G-CSF诱导骨髓中髓系分化的重编程,使TME中T细胞抑制性的N2型TANs数量增加。G-CSF还可以延长TANs的半衰期。TANs极化所带来的表型转换同时伴随着细胞因子和趋化因子等蛋白质分泌组谱的变化[24]。

3 TANs促进乳腺癌进展的作用机制

3.1 TANs能够促进乳腺癌细胞生长和转移

肿瘤源性GM-CSF能够激活TANs中的JAK/STAT5β信号转导通路,介导肿瘤细胞增殖调节因子转铁蛋白的分泌[25]。TANs分泌增殖诱导配体(A proliferation-induced ligand,APRIL)抑制乳腺癌细胞凋亡并驱动其增殖。肿瘤源性GM-CSF能够激活TANs的JAK/STAT5-C/EBPb信号转导通路,上调Acod1表达,促进衣康酸的合成并介导TANs的抗铁死亡效应,从而促进乳腺癌转移[26]。Ma等[27]在小鼠模型中揭示慢性肺部细菌感染通过上调CCL2的表达,募集主要组织相容性复合体Ⅱ类分子(major histocompatibility complex class Ⅱ molecule,MHCⅡ)高表达的TANs,促进乳腺癌细胞侵袭和肺转移。TANs还能够通过能量代谢参与肿瘤转移。Li等[28]在乳腺癌模型中研究发现TANs扮演着“肿瘤蓄电池”的角色,TANs在肺间充质细胞(mesenchymal cells,MCs)的诱导下增加中性脂肪的累积,并通过巨噬细胞-溶酶体途径将脂质转运到转移性肿瘤细胞中,赋予肿瘤细胞更强的生存和增殖能力。

3.2 TANs能够促进乳腺癌血管生成

肿瘤的持续生长需要肿瘤血管供给充足的营养成分并运输代谢废物,最近研究发现TANs在乳腺癌血管生成中也发挥重要作用。Ng等[29]对小鼠肿瘤模型TANs进行分析,定义浸润肿瘤的未成熟和成熟中性粒细胞分别分化为过渡性T1和T2亚群,两者重编程汇聚形成T3亚群,该亚群高表达诱饵TNF相关凋亡诱导配体-受体1(decoy TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand-receptor 1,dcTRAIL-R1)和血管内皮生长因子α(vascular endothelial growth factor α,VEGFα),加速肿瘤新生血管的形成,这种重编程对肿瘤细胞在低氧、氧化应激和代谢扰动TME的存活中发挥关键作用。TANs分泌的IL-17[30]和基质金属蛋白酶-9 (matrix metalloproteinase-9,MMP-9)[31]可发挥介导VEGF的释放和抑制抗血管生成因子的作用,推动乳腺癌血管生成。

3.3 TANs在乳腺癌中的免疫抑制作用

TANs通过与TME中的众多免疫细胞相互作用导致免疫抑制。通过重编程和控制T细胞的分化方向,TANs可抑制T细胞毒性。乳腺癌源性CCL20诱导TANs表达程序性死亡蛋白配体-1(programmed death ligand-1,PD-L1)[32],从而介导T细胞耗竭并促进肿瘤免疫逃逸,反之T细胞也可募集TANs并诱导其向N2型极化。TANs招募巨噬细胞和树突细胞到TME中并抑制自然杀伤(natural killer,NK)细胞的肿瘤杀伤作用[33]。Gong等[34]在肺转移的乳腺癌小鼠模型中发现肺组织中浸润的TANs对CD4+ 和CD8+ T细胞的增殖及NK细胞的细胞毒性具有显著抑制作用,TANs的这种免疫抑制能力在肿瘤相关炎症环境中得到加强,并且受到MCs的调控。

3.4 TANs形成中性粒细胞胞外诱捕网(neutrophil extracellular traps,NETs)

NETs是以DNA为骨架,镶嵌组蛋白和中性粒细胞弹性蛋白酶(neutrophil elastase,NE)、髓过氧化物酶(myeloperoxidase,MPO)等中性粒细胞衍生酶的网状复合结构[35]。中性粒细胞形成NETs的过程称为NETosis。不同于传统的凋亡和坏死,该过程是中性粒细胞的一种特殊的细胞死亡方式[36]。NETs在癌症的发生、发展中发挥重要作用,Zhang等[37]研究证实,NETs分数在大多数癌症(包括乳腺癌)中是高危因素,与多种恶性生物学过程如上皮-间充质转化(epithelial-mesenchymal transition,EMT)(R=0.744 4,P<0.000 1)、肿瘤血管生成(R=0.536 9,P<0.000 1)和肿瘤细胞增殖(R=0.383 5,P<0.000 1)显著相关。小鼠乳腺癌模型相关研究[38]发现,NETs是促进乳腺癌肝和肺转移的关键因素。值得注意的是,不同乳腺癌亚型中NETs的数量存在差异,其中TNBC中NETs的数量最多[36],此现象可能与TNBC中TANs表达率较高有关。值得注意的是NETs可以通过调节免疫细胞建立免疫抑制生态位[39],Teijeira等[40]在小鼠4T1乳腺癌模型中发现肿瘤源性CXCR1和CXCR2激动剂诱导, NETs的产生,NETs包裹肿瘤细胞,阻止其与免疫细胞接触,从而抑制细胞毒性T淋巴细胞(cytotoxic T lymphocyte,CTL)和NK细胞的肿瘤杀伤作用。肿瘤源性Chi3l1促进TANs的募集和NETs的形成,并直接诱导NETs的免疫抑制功能,从而抑制T细胞的募集[41]。Mousset等[42]研究发现,NETs在乳腺癌化疗耐药中也发挥着重要作用,化疗诱导癌细胞中的NLRP3活化并促进IL-1β分泌,诱导NETs的形成。NETs相关的整联蛋白αvβ1捕获肿瘤源性TGF-β并利用MMP-9使其激活,促进肿瘤细胞的EMT,从而降低乳腺癌肺转移的化疗效果,靶向IL-1β-NET-TGF-β轴的治疗为逆转转移性乳腺癌患者的化疗耐药提供 了可能。

与TANs在肿瘤发展中的双重潜能类似, NETs也具有促肿瘤和抗肿瘤的双重作用,这取决于免疫系统的状态以及与TME相互作用的结果[43]。但目前决定NETs功能的因素尚不明确。NETs组成的复杂性以及外周血和TME中NETs的较大异质性均为乳腺癌中靶向NETs治疗带来挑战。

4 TANs抑制乳腺癌进展的作用机制

4.1 TANs的直接抑制乳腺癌作用

TANs通过抗体依赖细胞介导的细胞毒性作用杀伤癌细胞[44],还可产生活性氧(reactive oxygen species,ROS)来氧化杀伤癌细胞或通过激活癌细胞的钙通道介导癌细胞凋亡[45]。然而ROS对癌症的作用存在剂量依赖性,在癌前病变和肿瘤进展的早期阶段,中等水平的ROS可诱导肿瘤的发生和转移。随着肿瘤进展,ROS水平超过毒性阈值会导致肿瘤细胞衰老和死亡[46]。TANs表达的TRAIL能够选择性诱导癌细胞凋亡,而对正常细胞无影响[47]。TANs通过分泌中性粒细胞弹性蛋白酶(neutrophil elastase,NE)并促使其水解,释放CD95的死亡结构域,从而选择性根除癌细胞[48]。

4.2 TANs的间接抑制乳腺癌作用

TANs作为先天性免疫和适应性免疫反应之间的桥梁,募集到TME后,参与NK细胞、淋巴细胞等多种免疫细胞复杂的双向作用[34]。TANs能够促进巨噬细胞产生IL-12,诱导CD4-CD8-非常规αβT细胞向分泌IFN-γ的抗肿瘤表型极化[49]。以CD86+或HLA-DR+CD74+[50]为特征的N1型TANs具有抗原呈递能力,可呈递肿瘤抗原至T细胞,重塑抗肿瘤T细胞克隆丰度并增强抗肿瘤应答效能,促进“热肿瘤”微环境的形成。TANs分泌的NE也可促进上述抗肿瘤响应过程,加速抗肿瘤CD8+ T细胞的活化动员[49]。

5 TANs在乳腺癌治疗中的潜能

5.1 TANs与乳腺癌治疗的临床相关性

近期临床研究[51]证实,高TANs密度与乳腺癌不良预后呈正相关,肿瘤间质(tumor stromal,TS)和瘤巢(tumor nests,TN)中均有TANs计数,且TS和TN中高TANs密度与肿瘤大小(TS:P=0.010;TN:P=0.001)、高组织学分级(TS:P<0.001;TN:P<0.001)和高淋巴结转移率(TS:P<0.001;TN:P<0.001)等多项乳腺癌不良预后指标均呈显著正相关。不同乳腺癌亚型中TANs的阳性表达率也有所差异,Soto-Perez-De-Celis等[6]研究发现,TNBC中TANs的阳性表达率为88%,人表皮生长因子受体2(human epidermal growth factor receptor 2,HER2)型为53%,Luminal A型为5%,多因素回归分析显示,TANs与激素受体的表达呈显著负相关[比值比(odds ratio,OR)=16.85,95% CI:4.4~64.6,P<0.000 1]。目前中性粒细胞与淋巴细胞比值(neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio,NLR)、TANs绝对计数及衍生因子水平常被用作各种癌症的预后指标[52]。多因素分析显示,NLR是TNBC患者无病生存率(disease-free survival,DFS)唯一的独立预后因素 [风险比(hazard ratio,HR)=2.60,95% CI:1.20~5.64,P=0.015][53]。NLR也是新辅助化疗(neoadjuvant-chemotherapy,NAC)治疗乳腺癌的预后预测指标,针对Luminal B型和HER2型乳腺癌的研究[54]发现,NAC的病理学完全缓解(pathological complete response,pCR)组的NLR显著高于非pCR组(P=0.048)。然而目前有关中性粒细胞的乳腺癌预后指标主要局限在循环中性粒细胞上,由于浸润在TME中的TANs的获取难度、肿瘤位置及分期差异,较难获得统一的预后指标。此外,TANs表型的多样性以及其在癌症中的双重潜能,使其在乳腺癌预后指标的探索中存在一定的争议。

5.2 抑制乳腺癌中TANs的浸润

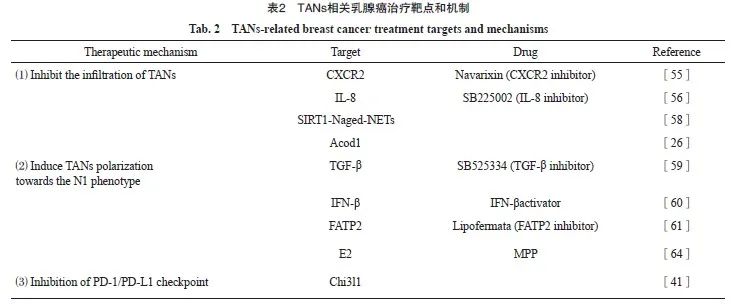

招募TANs是癌细胞利用中性粒细胞的第一步,TGF-β抑制剂与CXCR2拮抗剂Navarixin能够有效抑制TANs的浸润,并且已有CXCR2拮抗剂治疗乳腺癌的相关临床试验正在进行[55]。He等[56]研究发现,应用IL-8拮抗剂SB225002可显著消除TANs积累并延缓肿瘤生长。CXCR4是中性粒细胞运输的另一重要调节因子,参与TANs向转移前生态位的募集[57]。肿瘤相关衰老中性粒细胞(Naged,CXCR4+CD62Llow)通过SIRT1-Naged-NETs轴参与乳腺癌肺转移,CXCR4拮抗剂靶向Naged为预防乳腺癌肺转移提供了新策略[58]。由于TANs表型众多,靶向消除促肿瘤转移的TANs可显著增强乳腺癌治疗效果,然而对N2型TANs特异性治疗靶点的识别仍十分困难。

5.3 诱导TANs抗肿瘤极化

诱导TANs抗肿瘤极化,减少促肿瘤型TANs的数量,可显著削弱TANs的免疫抑制作用,增强乳腺癌的免疫治疗效果。阻断TGF-β[59]和增加IFN-β[60]等细胞因子可诱导TANs向N1型极化。脂肪酸转运蛋白2(fatty acid transport protein 2,FATP2)表达上调能够显著增强TANs的促瘤活性,选择性抑制FATP2可有效延缓肿瘤进展[61]。Linde等[62]研究发现,TNF、CD40激动剂和肿瘤结合抗体联合的鸡尾酒疗法可介导TANs中白三烯B4表达上调和ROS生成增加,激活TANs的抗肿瘤作用,该疗法对多种肿瘤(包括乳腺癌)有效。乳腺癌模型中雌二醇(estradiol,E2)通过诱导整联蛋白LFA-1过表达,促进TANs向N2极化[63],雌激素受体α (estrogen receptor α,ERα)拮抗剂甲基哌啶醇吡唑(methyl piperidol pyrazole,MPP)可削弱该作用从而抑制肿瘤进展[64]。诱导TANs向N2型重编程的疗法在乳腺癌治疗中的应用值得期待。

5.4 抑制TANs中程序性死亡蛋白-1(programmed death-1,PD-1)/PD-L1免疫检查点

靶向PD-1/PD-L1免疫检查点是一种有效的癌症免疫治疗方法,同样适用于靶向TANs的治疗[65]。有研究[66-67]表明,肿瘤源性IFN-γ、TNF-α和GM-CSF等细胞因子通过激活JAK-STAT3和IL6-STAT3等信号转导通路诱导TANs中PD-L1的表达。PD-L1+ TANs能够抑制T细胞和NK细胞的抗肿瘤免疫活性,加速肿瘤进展[68-69]。Taifour等[41]研究发现,TNBC中Chi3l1加速TANs招募,并通过调控PD-L1表达水平限制抗肿瘤免疫应答,从而降低PD-1/PD-L1抑制剂的疗效,靶向Chi3l1配合免疫治疗可显著提升TNBC的疗效。PD-1和PD-L1抑制剂已在乳腺癌治疗中广泛应用,而针对TANs靶点及TANs联合免疫检查点抑制剂的治疗值得期待。TANs相关乳腺癌治疗靶点和机制详见表2。

6 总结和展望

近年来TANs在乳腺癌中的分子机制和重要功能被逐渐揭示,TANs的多样性和可塑性意味着其不仅可在乳腺癌的发生、发展及免疫调控方面发挥重要作用,也有作为乳腺癌诊断标志物和免疫治疗靶点的潜能。现有研究证据证实, TANs在乳腺癌中具有抗肿瘤和促肿瘤的双重潜能,利用这种潜能进一步探究乳腺癌的新疗法前景可期。进一步探索TANs在乳腺癌中的功能机制,明确相关靶点,可以为乳腺癌的免疫治疗和免疫治疗联合放化疗提供新思路,最大程度地发挥TANs的治疗潜力,从而提高乳腺癌患者的生存获益。

利益冲突声明:所有作者均声明不存在利益冲突。

作者贡献声明:

徐睿:参与文章选题,文献和资料分析与解释,文章撰写和修改。

王泽浩:参与文章选题和修改,对文章的知识性内容作审阅。

吴炅:指导文章选题,对文章的知识性内容作审阅,获取研究经费。

[参考文献]

[1] NÉMETH T, SPERANDIO M, MÓCSAI A. Neutrophils as emerging therapeutic targets[J]. Nat Rev Drug Discov, 2020, 19(4): 253-275.

[2] JAILLON S, PONZETTA A, MITRI D D, et al. Neutrophil diversity and plasticity in tumour progression and therapy[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2020, 20(9): 485-503.

[3] CHEN S, ZHANG Q Y, LU L S, et al. Heterogeneity of neutrophils in cancer: one size does not fit all[J]. Cancer Biol Med, 2022, 19(12): 1629-1648.

[4] BARRY S T, GABRILOVICH D I, SANSOM O J, et al. Therapeutic targeting of tumour myeloid cells[J]. Nat Rev Cancer, 2023, 23(4): 216-237.

[5] SUNG H, FERLAY J, SIEGEL R L, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries[J]. CA Cancer J Clin, 2021, 71(3): 209-249.

[6] SOTO-PEREZ-DE-CELIS E, CHAVARRI-GUERRA Y, LEON-RODRIGUEZ E, et al. Tumor-associated neutrophils in breast cancer subtypes[J]. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 2017, 18(10): 2689-2693.

[7] HIDALGO A, CHILVERS E R, SUMMERS C, et al. The neutrophil life cycle[J]. Trends Immunol, 2019, 40(7): 584-597.

[8] FURZE R C, RANKIN S M. Neutrophil mobilization and clearance in the bone marrow[J]. Immunology, 2008, 125(3): 281-288.

[9] LEY K, HOFFMAN H M, KUBES P, et al. Neutrophils: new insights and open questions[J]. Sci Immunol, 2018, 3(30): eaat4579.

[10] ADROVER J M, DEL FRESNO C, CRAINICIUC G, et al. A neutrophil timer coordinates immune defense and vascular protection[J]. Immunity, 2019, 51(5): 966-967.

[11] LOH W, VERMEREN S. Anti-inflammatory neutrophil functions in the resolution of inflammation and tissue repair

[J]. Cells, 2022, 11(24): 4076.

[12] ALLEN S J, CROWN S E, HANDEL T M. Chemokine: receptor structure, interactions, and antagonism[J]. Annu Rev Immunol, 2007, 25: 787-820.

[13] FOUSEK K, HORN L A, PALENA C. Interleukin-8: a chemokine at the interp of cancer plasticity, angiogenesis, and immune suppression[J]. Pharmacol Ther, 2021, 219: 107692.

[14] HE K, LIU X, HOFFMAN R D, et al. G-CSF/GM-CSFinduced hematopoietic dysregulation in the progression of solid tumors[J]. FEBS Open Bio, 2022, 12(7): 1268-1285.

[15] XU Y L, YAN J X, TAO Y, et al. Pituitary hormone α-MSH promotes tumor-induced myelopoiesis and immunosuppression[J]. Science, 2022, 377(6610): 1085-1091.

[16] NOURSHARGH S, RENSHAW S A, IMHOF B A. Reverse migration of neutrophils: where, when, how, and why? [J]. Trends Immunol, 2016, 37(5): 273-286.

[17] CORTEZ-RETAMOZO V, ETZRODT M, NEWTON A, et al. Origins of tumor-associated macrophages and neutrophils[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2012, 109(7): 2491-2496.

[18] FRIDLENDER Z G, SUN J, KIM S, et al. Polarization of tumorassociated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-beta: “N1” versus “N2” TAN[J]. Cancer Cell, 2009, 16(3): 183-194.

[19] YU X Y, LI C H, WANG Z J, et al. Neutrophils in cancer: dual roles through intercellular interactions[J]. Oncogene, 2024, 43(16): 1163-1177.

[20] POETA V M, MASSARA M, CAPUCETTI A, et al. Chemokines and chemokine receptors: new targets for cancer immunotherapy[J]. Front Immunol, 2019, 10: 379.

[21] OHMS M, MÖLLER S, LASKAY T. An attempt to polarize human neutrophils toward N1 and N2 phenotypes in vitro[J]. Front Immunol, 2020, 11: 532.

[22] LIU S Y, WU W C, DU Y S, et al. The evolution and heterogeneity of neutrophils in cancers: origins, subsets, functions, orchestrations and clinical applications[J]. Mol Cancer, 2023, 22(1): 148.

[23] CASBON A J, REYNAUD D, PARK C, et al. Invasive breast cancer reprograms early myeloid differentiation in the bone marrow to generate immunosuppressive neutrophils[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2015, 112(6): E566-E575.

[24] QUE H Y, FU Q M, LAN T X, et al. Tumor-associated neutrophils and neutrophil-targeted cancer therapies[J]. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer, 2022, 1877(5): 188762.

[25] LIANG W, LI Q, FERRARA N. Metastatic growth instructed by neutrophil-derived transferrin[J]. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2018, 115(43): 11060-11065.

[26] ZHAO Y, LIU Z S, LIU G Q, et al. Neutrophils resist ferroptosis and promote breast cancer metastasis through aconitate decarboxylase 1[J]. Cell Metab, 2023, 35(10): 1688-1703. e10.

[27] MA T, TANG Y, WANG T L, et al. Chronic pulmonary bacterial infection facilitates breast cancer lung metastasis by recruiting tumor-promoting MHCⅡhi neutrophils[J]. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2023, 8(1): 296.

[28] LI P S, LU M, SHI J Y, et al. Lung mesenchymal cells elicit lipid storage in neutrophils that fuel breast cancer lung metastasis[J]. Nat Immunol, 2020, 21(11): 1444-1455.

[29] NG M S F, KWOK I, TAN L, et al. Deterministic reprogramming of neutrophils within tumors[J]. Science, 2024, 383(6679): eadf6493.

[30] LI T J, JIANG Y M, HU Y F, et al. Interleukin-17-producing neutrophils link inflammatory stimuli to disease progression by promoting angiogenesis in gastric cancer[J]. Clin Cancer Res, 2017, 23(6): 1575-1585.

[31] LIU Z L, CHEN H H, ZHENG L L, et al. Angiogenic signaling pathways and anti-angiogenic therapy for cancer[J]. Signal Transduct Target Ther, 2023, 8(1): 198.

[32] KWANTWI L B, WANG S J, ZHANG W J, et al. Tumorassociated neutrophils activated by tumor-derived CCL20 (C-C motif chemokine ligand 20) promote T cell immunosuppression via programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) in breast cancer[J]. Bioengineered, 2021, 12(1): 6996-7006.

[33] SPIEGEL A, BROOKS M W, HOUSHYAR S, et al. Neutrophils suppress intraluminal NK cell-mediated tumor cell clearance and enhance extravasation of disseminated carcinoma cells[J]. Cancer Discov, 2016, 6(6): 630-649.

[34] G O N G Z , L I Q , S H I J Y , e t a l . I mmu n o s u p p r e s s i v e reprogramming of neutrophils by lung mesenchymal cells promotes breast cancer metastasis[J]. Sci Immunol, 2023,

8(80): eadd5204.

[35] SHAO B Z, YAO Y, LI J P, et al. The role of neutrophil extracellular traps in cancer[J]. Front Oncol, 2021, 11: 714357.

[36] MASUCCI M T, MINOPOLI M, DEL VECCHIO S, et al. The emerging role of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in tumor progression and metastasis[J]. Front Immunol, 2020, 11: 1749.

[37] ZHANG Y, GUO L P, DAI Q C, et al. A signature for pancancer prognosis based on neutrophil extracellular traps[J]. J Immunother Cancer, 2022, 10(6): e004210.

[38] HSU B E, TABARIÈS S, JOHNSON R M, et al. Immature lowdensity neutrophils exhibit metabolic flexibility that facilitates breast cancer liver metastasis[J]. Cell Rep, 2019, 27(13): 3902-3915.e6.

[39] WANG Y G, DING Y X, GUO N Z, et al. MDSCs: key criminals of tumor pre-metastatic niche formation[J]. Front Immunol, 2019, 10: 172.

[40] TEIJEIRA Á, GARASA S, GATO M, et al. CXCR1 and CXCR2 chemokine receptor agonists produced by tumors induce neutrophil extracellular traps that interfere with immune cytotoxicity[J]. Immunity, 2020, 52(5): 856-871.e8.

[41] TAIFOUR T, ATTALLA S S, ZUO D M, et al. The tumorderived cytokine Chi3l1 induces neutrophil extracellular traps that promote T cell exclusion in triple-negative breast cancer[J]. Immunity, 2023, 56(12): 2755-2772.e8.

[42] MOUSSET A, LECORGNE E, BOURGET I, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps formed during chemotherapy confer treatment resistance via TGF-β activation[J]. Cancer Cell, 2023, 41(4): 757-775.e10.

[43] SCHEDEL F, MAYER-HAIN S, PAPPELBAUM K I, et al. Evidence and impact of neutrophil extracellular traps in malignant melanoma[J]. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res, 2020, 33(1): 63-73.

[44] FURUMAYA C, MARTINEZ-SANZ P, BOUTI P, et al. Plasticity in pro- and anti-tumor activity of neutrophils: Shifting the balance[J]. Front Immunol, 2020, 11: 2100.

[45] GERSHKOVITZ M, CASPI Y, FAINSOD-LEVI T, et al. TRPM2 mediates neutrophil killing of disseminated tumor cells[J]. Cancer Res, 2018, 78(10): 2680-2690.

[46] AGGARWAL V, TULI H S, VAROL A, et al. Role of reactive oxygen species in cancer progression: molecular mechanisms and recent advancements[J]. Biomolecules, 2019, 9(11): 735.

[47] DENG D, SHAH K. TRAIL of hope meeting resistance in cancer[J]. Trends Cancer, 2020, 6(12): 989-1001.

[48] CUI C, CHAKRABORTY K, TANG X A, et al. Neutrophil elastase selectively kills cancer cells and attenuates tumorigenesis[J]. Cell, 2021, 184(12): 3163-3177.e21.

[49] PONZETTA A, CARRIERO R, CARNEVALE S, et al. Neutrophils driving unconventional T cells mediate resistance against murine sarcomas and selected human tumors[J]. Cell, 2019, 178(2): 346-360.e24.

[50] WU Y C, MA J Q, YANG X P, et al. Neutrophil profiling illuminates anti-tumor antigen-presenting potency[J]. Cell, 2024, 187(6): 1422-1439.e24.

[51] KAKUMOTO A, JAMIYAN T, KURODA H, et al. Prognostic impact of tumor-associated neutrophils in breast cancer[J]. Int J Clin Exp Pathol, 2024, 17(3): 51-62.

[52] PU N, YIN H L, ZHAO G C, et al. Independent effect of postoperative neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio on the survival of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with open distal pancreatosplenectomy and its nomogram-based prediction[J]. J Cancer, 2019, 10(24): 5935-5943.

[53] HUANG Z N, LI Z X, YAO Z C, et al. Clinical prognostic evaluation of immunocytes in different molecular subtypes of breast cancer[J]. J Cell Physiol, 2019, 234(11): 20584-20602.

[54] VON AU A, SHENCORU S, UHLMANN L, et al. Predictive value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte-ratio in neoadjuvant treated patients with breast cancer[J]. Arch Gynecol Obstet, 2023, 307(4): 1105-1113.

[55] ZHANG X, GE X, JIANG T, et al. Research progress on immunotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer (Review)[J]. Int J Oncol, 2022, 61(2): 95.

[56] HE J, ZHOU M X, YIN J, et al. METTL3 restrains papillary thyroid cancer progression via m6A/c-Rel/IL-8-mediated neutrophil infiltration[J]. Mol Ther, 2021, 29(5): 1821-1837.

[57] LIN Q, FANG X L, LIANG G H, et al. Silencing CTNND1 mediates triple-negative breast cancer bone metastasis via upregulating CXCR4/CXCL12 axis and neutrophils infiltration in bone[J]. Cancers, 2021, 13(22): 5703.

[58] YANG C H, WANG Z, LI L L, et al. Aged neutrophils form mitochondria-dependent vital NETs to promote breast cancer lung metastasis[J]. J Immunother Cancer, 2021, 9(10): e002875.

[59] PENG H M, SHEN J, LONG X, et al. Local release of TGF-β inhibitor modulates tumor-associated neutrophils and enhances pancreatic cancer response to combined irreversible electroporation and immunotherapy[J]. Adv Sci, 2022, 9(10): e2105240.

[60] YU R R, ZHU B, CHEN D G. Type I interferon-mediated tumor immunity and its role in immunotherapy[J]. Cell Mol Life Sci, 2022, 79(3): 191.

[61] VEGLIA F, TYURIN V A, BLASI M, et al. Fatty acid transport protein 2 reprograms neutrophils in cancer[J]. Nature, 2019, 569(7754): 73-78.

[62] LINDE I L, PRESTWOOD T R, QIU J T, et al. Neutrophilactivating therapy for the treatment of cancer[J]. Cancer Cell, 2023, 41(2): 356-372.e10.

[63] VAZQUEZ RODRIGUEZ G, ABRAHAMSSON A, JENSEN L D, et al. Estradiol promotes breast cancer cell migration via recruitment and activation of neutrophils[J]. Cancer Immunol Res, 2017, 5(3): 234-247.

[64] MINOR B M N, LEMOINE D, SEGER C, et al. Estradiol augments tumor-induced neutrophil production to promote tumor cell actions in lymphangioleiomyomatosis models[J]. Endocrinology, 2023, 164(6): bqad061.

[65] DAASSI D, MAHONEY K M, FREEMAN G J. The importance of exosomal PD-L1 in tumour immune evasion[J]. Nat Rev Immunol, 2020, 20(4): 209-215.

[66] WANG T T, ZHAO Y L, PENG L S, et al. Tumour-activated neutrophils in gastric cancer foster immune suppression and disease progression through GM-CSF-PD-L1 pathway[J]. Gut, 2017, 66(11): 1900-1911.

[67] KHOU S, POPA A, LUCI C, et al. Tumor-associated neutrophils dampen adaptive immunity and promote cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma development[J]. Cancers, 2020, 12(7): 1860.

[68] ZHAO Y, BAI Y S, SHEN M L, et al. Therapeutic strategies for gastric cancer targeting immune cells: future directions[J]. Front Immunol, 2022, 13: 992762.

[69] SUN R, XIONG Y Y, LIU H J, et al. Tumor-associated neutrophils suppress antitumor immunity of NK cells through the PD-L1/PD-1 axis[J]. Transl Oncol, 2020, 13(10): 100825.